Material Nomads

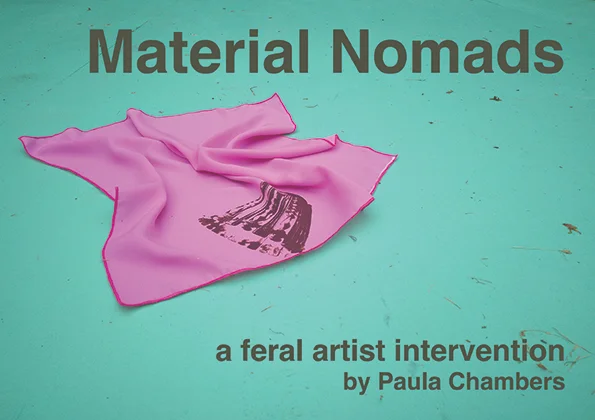

Material Nomads, a feral artist intervention by Paula Chambers

When I first visited Norway in 2004, I purchased a white plastic coffee jug which I gifted to my mother upon my return to the UK. In subsequent years I have bought numerous other small domestic objects from flea markets and second-hand shops in towns and cities across Europe, sometimes these objects get incorporated into sculptural works, sometimes they don’t. On a recent visit to my mother, she gave me back the white plastic coffee jug I had gifted to her all those years ago, and as I travelled the four-hundred miles back to Leeds I reflected on the journeys this fairly insignificant object had made, and on those undertaken by all the other bits of domestic ephemera I had accumulated over the years. I have come to think of these objects as nomadic, the black and white plastic hand mirror I had bought from a flea market in Porto, the small pink glass vase from a second-hand shop in Arles, a creamy coloured crinoline lady dressing table brush from the famous Jeu de Balle flea market in Brussels, the strange clear resin ornament from a side street junk shop in Riga, it is these and many other such objects that became the Material Nomads of this project’s title.

Nomadism is not aimless wandering, but is rather a methodical rotation of settlements to ensure maximum use of obtainable resources. Nomadism is a spatialised condition of flux where movement is triggered and sustained by various key material actants. Nomads, Judith Okely (2014) argues “…have tended to use movement and invisibility for political/economic survival in the midst of a sedentarist polity. Evasion and unpredictability have hitherto been creative, productive strategies” (p.67). Similarly, the process of collecting, journeying, transforming, installing and documenting my Material Nomads has been a productive strategy that is at times both unpredictable and to a certain extent evasive. At the airport I did not declare that I had art work in my suitcase and I did not ask for anyone’s permission to install and document the works in any of the locations.

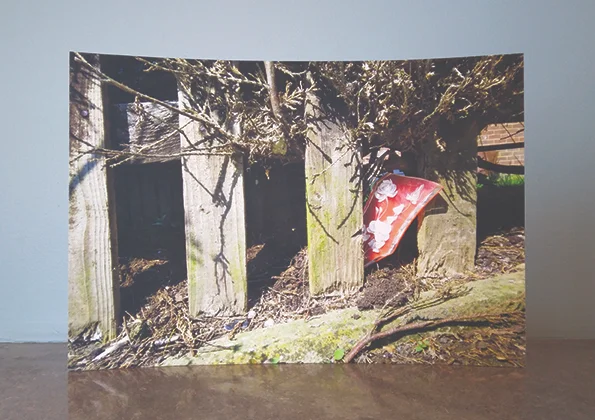

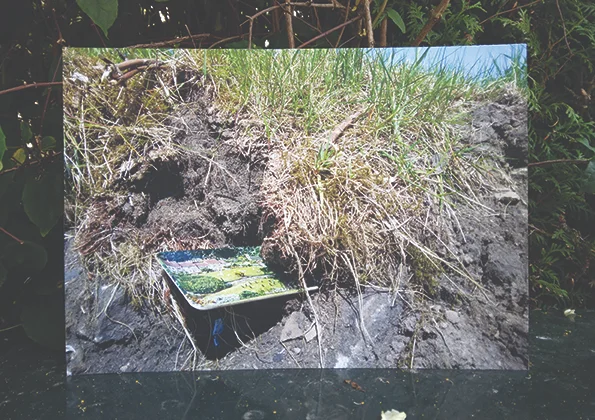

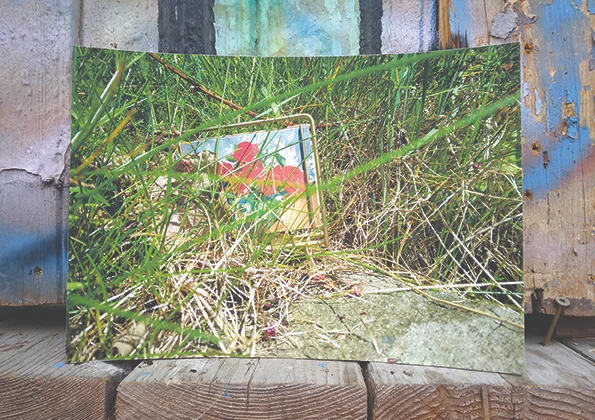

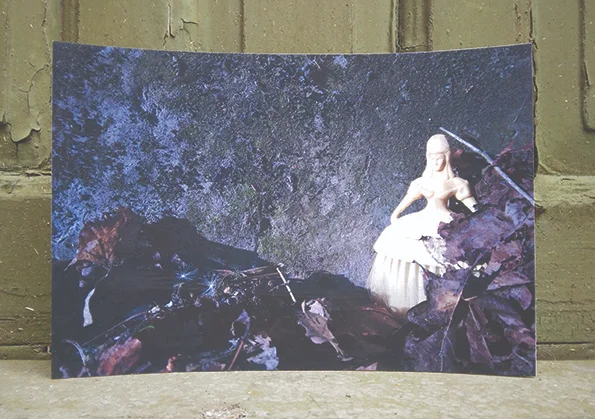

When asked to participate in Momentum 12, I responded to the biennale title ‘Together as to Gather’ and the collaborative ethos of the Tenthaus curatorial team through a conceptual gathering together of the tribe of objects with which I collaborate as sculptural practice. I decided to undertake a feral artist intervention, to continue the nomadic journeying of my objects by bringing them with me to Norway. The objects underwent a series of sculptural processes, each of which removed them once step away from their original form, as a kind of material distancing. I photographed each of the objects loitering in locations around the housing estate where I live, in the kind of liminal locations favoured by feral animals, spaces not too domesticated, yet not entirely wild. The resulting images were printed A4 size and mounted on to board. I used individual images of the objects to produce a series of pink chiffon squares, a bit like ladies’ scarves, the objects depicted off centre and sort of escaping from the overlocked borders of the fabric. I then took relief castings of each of the objects in paper-mâché and copper foil finished with a fluorescent pink posterior surface. There were seventeen original objects, each resulted in three material outcomes, so I took with me to Norway fifty-one artworks packed in a standard sized suitcase. I stayed five days in Moss during which time I installed and documented each of the fifty-one artworks in locations in and around the town and surrounding areas of Jeløya, including the gallery spaces and grounds of Galleri F15 where the Momentum 12 exhibition was primarily being hosted. Material Nomads occupied spaces and places beyond the parameters of the cultural institution, this was a feral artist intervention that took material form not entirely independent from, but was rather as an intentional process of scavenging on the peripheries of the art world.

Most of the objects whose journeys were materialised as the art works of this project are made from plastic, a much-maligned modern material due to its negative environmental impact, primarily in its form as waste. Waste, William Viney (2015) argues, can be defined in relation to its temporality, stuff becomes waste due to breakage, being used up or left over, coming end of its lifespan etc. nothing starts off as waste. Evidence of particles of plastic in the food chain has been presented by the media within a sensationalist narrative of bodily invasion, language that in many ways is not dissimilar to that used to describe the migration of people. Nomads are often seen as threatening, they are vulnerable to demonisation and are often feared as menacing invaders (Okely, 2014). An understanding of the migration of plastics from useful to invasive is both an historical narrative and a politicised position, plastic has become a material scapegoat of the climate crisis. Despite this (or maybe because of this) I like plastic, it is hard wearing and versatile, it is the material most commonly used for the production of low-cost domestic products, and comes in a range of attractive colours.

In the last few years, I have been creating sculptural works predominantly from copper and various found materials that are pink. The colour pink has since the 1950s become a coding for femininity, likewise for me as a sculptor using objects and materials that are pink acts as a shorthand for femininity. Copper is an interesting material, it seems to me to have magical qualities in its ability to change colour from a lovely pinkish brown when new and polished, to the classic blueish green seen outdoors and on buildings. Up close oxidised copper often has a salty white crust which sometimes contains a range of deep blue and green pigments which are really very beautiful. Copper is used for plumbing, lengths of pipe of differing circumferences, and small fixings in a range of shapes can be bought fairly cheaply in any good DIY store. For an artist who predominantly makes all their work in their living room and kitchen, copper has the advantage of coming as thin sheets which can be cut and shaped by hand, sometimes it even has a handy self-adhesive backing! Copper is also a superb conductor, hence it’s ubiquitous use in electrical wiring. Jane Bennett (2010) in her analysis of matter as active and vibrant, presents electricity as an actant with emphasis on how the irregular crystalline structure of metals allows for unreliable conductivity. “Electricity sometimes goes where we send it, and sometimes it chooses its path on the spot, in response to the other bodies it encounters and the surprising opportunities for actions and interactions that they afford” (p.28). Copper is a material that is ideal for a feminist domestic sculptural practice, and proved materially and conceptually ideal also for my Material Nomads. Chiffon is also a really lovely material to work with, and although the specific chiffon I used for Material Nomads is entirely synthetic (due to the need to use a heat press to transfer the object images), it still has the touch and feel, and flows through the hand, like traditional chiffon. When I was a girl my mother owned many chiffon head scarves in a range of pastel colours, she would tie these over her hair to keep her rollers in, a practice that has become popular again in recent years. I encountered a group of just such young women at Manchester airport as I was waiting for my flight to Oslo, they were off to a hen party in Malaga, all had their hair in enormous rollers and each had these covered in a brightly coloured chiffon scarf.

During my stay in Moss during I explored the urban and rural areas of the town and the island of Jeløya at some length, looking always with the potential for display in mind. I walked the side streets of housing areas and town centre, visited churches and historic buildings. I went to the beach in several different parts of the island, observing wildlife and construction works with equal fascination. I walked through woodland and along rural footpaths, encountering runners, dog walkers and several groups of school children. I explored the immediate area around the hostel where I was staying and discovered a plethora of street furniture, fire pits and quaint Nordic holiday cottages, there was even a mobile sauna! And I visited Galleri F15 in Alby, a short twenty-minute walk from my accommodation, to see the Momentum 12 exhibition and to undertake feral interventions in and around the gallery space. In each of these locations and over the five days of my exploration, I installed and documented the fifty-one works that comprise Material Nomads. Due to their relative solidity, the copper works could ‘hold’ slots in wooden fences or metal meshwork, could sometimes balance on their curved edges or hang off outcrops of rock or other ledges. The chiffon squares required at least one corner to be wedged or fastened into a pre-existing gap, or to be hung over something that would allow for the object image to be visible. The A4 boards were free-standing due to their (accidental) curved nature. These I chose to install and document standing on a range of flat surfaces – indoors and out – like found object plinths, as if they were part of an exhibition.

Previously I have worked with what I term feral objects, the objects and materials of feminine domesticity that are no longer in use for their intended purpose. My feral objects are those sourced in the liminal consumer spaces of flea markets, second-hand shops, car boot sales and roadside collection. To be feral usually implies an escape from domestication, although it could also imply abandonment and vulnerability. Ferals have been left to fend for themselves, they have not subordinated to human control. They may have migrated opportunistically, or as with animals such as foxes, squirrels and sea gulls, adapted to life in human-built environments. Although sometimes thought of as illegitimate, as aliens, pests or trespassers in human environments, (feral animals are) in many ways similar to human denizens who, for various reasons wish or need to live in places where they do not feel they belong, or in whose political processes they do not wish to participate (Struthers Montford and Taylor 2016). Feral can be understood in this context as a feminist position, whereby sexual oppression is the historical domestication of the human female, undoing gender therefore is to become feral. Feral theory questions who has the right to be (or to belong) here/or there, feral objects, and by extension, feral artist interventions allow for evasion and unpredictability, for creative resistance to systems of control and for the potential to undertake opportunistic art working strategies.

Angela Dimitriakaki (2014) proposes feminist art working strategies as practices of refusal, particularly in relation to the feminisation of migratory labour and to the labour of the woman artist. “…in the realm of art committed to radical politics by example (by how and where artists act), the main dilemma faced is whether to opt for situating such action in a grey zone between work and non-work – since artists receive wages from other forms of labour” (p.159). It is my proposition that it is in this grey zone that feral actions take place, a feral artist intervention is both work and non-work, and is undertaken in spaces and places that are peripheral to, yet in the geographical location of, and partially supported by, the art gallery, museum or cultural institution. Despite the ongoing efforts of academic feminism, access to the privileged spaces of the museum and art gallery, (and associated critical review as a means for visibility within art history) remain out of bounds for many women artists. A feral artist intervention such as that undertaken for Momentum 12 is what Dimitrakaki understands as “…the projects of positive feminisation…(which) can also be seen as platforms where critical forms of visibility are pursued” (p.160). Although my university paid for my flights to Norway as part of my research funding, I had imagined that the rest of my trip would be self-funded. What actually happened was that people from Tenthaus were extraordinarily generous and kept me fed and entertained during my time in Moss. Additionally, as part of the Momentum 12 workshop program, I attended the feral business training camp where alternative economic and cultural work models were explored. The workshop held an arbitrary raffle where the winner would take away an undisclosed sum of cash to put towards their business venture, miraculously I won and it was this money that paid for the production of the publication I produced.

References

Bennett, Jane (2010) Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London, Duke University Press

Dimitrakaki, Angela (2014) Leaving Home: Stories of Feminisation, Work and Non-Work, in Critical Cartography of Art and Visibility in the Global Age. Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp 145-160

Okely, Judith (2014) Recycled (Mis)representations: Gypsies, Travellers or Roma Treated as Objects, Rarely Subjects. in People, Place and Policy 8/1, pp. 65-85 (accessed 14th July 2023)

Struthers Montford, Kelly and Taylor, Chloë (2016) Feral Theory, Editor’s Introduction. In Feral Feminisms, issue 6, fall 2016 https://feralfeminisms.com/feralintroduction/ (accessed 18th July 2023)

Viney, William (2015) Waste: A Philosophy of Things. London, Bloomsbury

Nomadism is not aimless wandering, but is rather a methodical rotation of settlements to ensure maximum use of obtainable resources. Nomadism is a spatialised condition of flux where movement is triggered and sustained by various key material actants. Nomads, Judith Okely (2014) argues “…have tended to use movement and invisibility for political/economic survival in the midst of a sedentarist polity. Evasion and unpredictability have hitherto been creative, productive strategies” (p.67). Similarly, the process of collecting, journeying, transforming, installing and documenting my Material Nomads has been a productive strategy that is at times both unpredictable and to a certain extent evasive. At the airport I did not declare that I had art work in my suitcase and I did not ask for anyone’s permission to install and document the works in any of the locations.

When asked to participate in Momentum 12, I responded to the biennale title ‘Together as to Gather’ and the collaborative ethos of the Tenthaus curatorial team through a conceptual gathering together of the tribe of objects with which I collaborate as sculptural practice. I decided to undertake a feral artist intervention, to continue the nomadic journeying of my objects by bringing them with me to Norway. The objects underwent a series of sculptural processes, each of which removed them once step away from their original form, as a kind of material distancing. I photographed each of the objects loitering in locations around the housing estate where I live, in the kind of liminal locations favoured by feral animals, spaces not too domesticated, yet not entirely wild. The resulting images were printed A4 size and mounted on to board. I used individual images of the objects to produce a series of pink chiffon squares, a bit like ladies’ scarves, the objects depicted off centre and sort of escaping from the overlocked borders of the fabric. I then took relief castings of each of the objects in paper-mâché and copper foil finished with a fluorescent pink posterior surface. There were seventeen original objects, each resulted in three material outcomes, so I took with me to Norway fifty-one artworks packed in a standard sized suitcase. I stayed five days in Moss during which time I installed and documented each of the fifty-one artworks in locations in and around the town and surrounding areas of Jeløya, including the gallery spaces and grounds of Galleri F15 where the Momentum 12 exhibition was primarily being hosted. Material Nomads occupied spaces and places beyond the parameters of the cultural institution, this was a feral artist intervention that took material form not entirely independent from, but was rather as an intentional process of scavenging on the peripheries of the art world.

Most of the objects whose journeys were materialised as the art works of this project are made from plastic, a much-maligned modern material due to its negative environmental impact, primarily in its form as waste. Waste, William Viney (2015) argues, can be defined in relation to its temporality, stuff becomes waste due to breakage, being used up or left over, coming end of its lifespan etc. nothing starts off as waste. Evidence of particles of plastic in the food chain has been presented by the media within a sensationalist narrative of bodily invasion, language that in many ways is not dissimilar to that used to describe the migration of people. Nomads are often seen as threatening, they are vulnerable to demonisation and are often feared as menacing invaders (Okely, 2014). An understanding of the migration of plastics from useful to invasive is both an historical narrative and a politicised position, plastic has become a material scapegoat of the climate crisis. Despite this (or maybe because of this) I like plastic, it is hard wearing and versatile, it is the material most commonly used for the production of low-cost domestic products, and comes in a range of attractive colours.

In the last few years, I have been creating sculptural works predominantly from copper and various found materials that are pink. The colour pink has since the 1950s become a coding for femininity, likewise for me as a sculptor using objects and materials that are pink acts as a shorthand for femininity. Copper is an interesting material, it seems to me to have magical qualities in its ability to change colour from a lovely pinkish brown when new and polished, to the classic blueish green seen outdoors and on buildings. Up close oxidised copper often has a salty white crust which sometimes contains a range of deep blue and green pigments which are really very beautiful. Copper is used for plumbing, lengths of pipe of differing circumferences, and small fixings in a range of shapes can be bought fairly cheaply in any good DIY store. For an artist who predominantly makes all their work in their living room and kitchen, copper has the advantage of coming as thin sheets which can be cut and shaped by hand, sometimes it even has a handy self-adhesive backing! Copper is also a superb conductor, hence it’s ubiquitous use in electrical wiring. Jane Bennett (2010) in her analysis of matter as active and vibrant, presents electricity as an actant with emphasis on how the irregular crystalline structure of metals allows for unreliable conductivity. “Electricity sometimes goes where we send it, and sometimes it chooses its path on the spot, in response to the other bodies it encounters and the surprising opportunities for actions and interactions that they afford” (p.28). Copper is a material that is ideal for a feminist domestic sculptural practice, and proved materially and conceptually ideal also for my Material Nomads. Chiffon is also a really lovely material to work with, and although the specific chiffon I used for Material Nomads is entirely synthetic (due to the need to use a heat press to transfer the object images), it still has the touch and feel, and flows through the hand, like traditional chiffon. When I was a girl my mother owned many chiffon head scarves in a range of pastel colours, she would tie these over her hair to keep her rollers in, a practice that has become popular again in recent years. I encountered a group of just such young women at Manchester airport as I was waiting for my flight to Oslo, they were off to a hen party in Malaga, all had their hair in enormous rollers and each had these covered in a brightly coloured chiffon scarf.

During my stay in Moss during I explored the urban and rural areas of the town and the island of Jeløya at some length, looking always with the potential for display in mind. I walked the side streets of housing areas and town centre, visited churches and historic buildings. I went to the beach in several different parts of the island, observing wildlife and construction works with equal fascination. I walked through woodland and along rural footpaths, encountering runners, dog walkers and several groups of school children. I explored the immediate area around the hostel where I was staying and discovered a plethora of street furniture, fire pits and quaint Nordic holiday cottages, there was even a mobile sauna! And I visited Galleri F15 in Alby, a short twenty-minute walk from my accommodation, to see the Momentum 12 exhibition and to undertake feral interventions in and around the gallery space. In each of these locations and over the five days of my exploration, I installed and documented the fifty-one works that comprise Material Nomads. Due to their relative solidity, the copper works could ‘hold’ slots in wooden fences or metal meshwork, could sometimes balance on their curved edges or hang off outcrops of rock or other ledges. The chiffon squares required at least one corner to be wedged or fastened into a pre-existing gap, or to be hung over something that would allow for the object image to be visible. The A4 boards were free-standing due to their (accidental) curved nature. These I chose to install and document standing on a range of flat surfaces – indoors and out – like found object plinths, as if they were part of an exhibition.

Previously I have worked with what I term feral objects, the objects and materials of feminine domesticity that are no longer in use for their intended purpose. My feral objects are those sourced in the liminal consumer spaces of flea markets, second-hand shops, car boot sales and roadside collection. To be feral usually implies an escape from domestication, although it could also imply abandonment and vulnerability. Ferals have been left to fend for themselves, they have not subordinated to human control. They may have migrated opportunistically, or as with animals such as foxes, squirrels and sea gulls, adapted to life in human-built environments. Although sometimes thought of as illegitimate, as aliens, pests or trespassers in human environments, (feral animals are) in many ways similar to human denizens who, for various reasons wish or need to live in places where they do not feel they belong, or in whose political processes they do not wish to participate (Struthers Montford and Taylor 2016). Feral can be understood in this context as a feminist position, whereby sexual oppression is the historical domestication of the human female, undoing gender therefore is to become feral. Feral theory questions who has the right to be (or to belong) here/or there, feral objects, and by extension, feral artist interventions allow for evasion and unpredictability, for creative resistance to systems of control and for the potential to undertake opportunistic art working strategies.

Angela Dimitriakaki (2014) proposes feminist art working strategies as practices of refusal, particularly in relation to the feminisation of migratory labour and to the labour of the woman artist. “…in the realm of art committed to radical politics by example (by how and where artists act), the main dilemma faced is whether to opt for situating such action in a grey zone between work and non-work – since artists receive wages from other forms of labour” (p.159). It is my proposition that it is in this grey zone that feral actions take place, a feral artist intervention is both work and non-work, and is undertaken in spaces and places that are peripheral to, yet in the geographical location of, and partially supported by, the art gallery, museum or cultural institution. Despite the ongoing efforts of academic feminism, access to the privileged spaces of the museum and art gallery, (and associated critical review as a means for visibility within art history) remain out of bounds for many women artists. A feral artist intervention such as that undertaken for Momentum 12 is what Dimitrakaki understands as “…the projects of positive feminisation…(which) can also be seen as platforms where critical forms of visibility are pursued” (p.160). Although my university paid for my flights to Norway as part of my research funding, I had imagined that the rest of my trip would be self-funded. What actually happened was that people from Tenthaus were extraordinarily generous and kept me fed and entertained during my time in Moss. Additionally, as part of the Momentum 12 workshop program, I attended the feral business training camp where alternative economic and cultural work models were explored. The workshop held an arbitrary raffle where the winner would take away an undisclosed sum of cash to put towards their business venture, miraculously I won and it was this money that paid for the production of the publication I produced.

References

Bennett, Jane (2010) Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London, Duke University Press

Dimitrakaki, Angela (2014) Leaving Home: Stories of Feminisation, Work and Non-Work, in Critical Cartography of Art and Visibility in the Global Age. Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp 145-160

Okely, Judith (2014) Recycled (Mis)representations: Gypsies, Travellers or Roma Treated as Objects, Rarely Subjects. in People, Place and Policy 8/1, pp. 65-85 (accessed 14th July 2023)

Struthers Montford, Kelly and Taylor, Chloë (2016) Feral Theory, Editor’s Introduction. In Feral Feminisms, issue 6, fall 2016 https://feralfeminisms.com/feralintroduction/ (accessed 18th July 2023)

Viney, William (2015) Waste: A Philosophy of Things. London, Bloomsbury